Francis Shuler [“Francis Shuller”]

On the 15th of May, 1766, “Valentine Shuler [“Vallentin Schuller”] of Tulpehocken Township, Yeoman, eldest son and heir at law of Francis Shuler” petitioned a Berks county Orphans’ Court held at Reading by Justices Jonas Seely, Peter Spycker and Henry Christ, Esquires, for an inquest to partition or value his father’s land. No other primary source to date connects father to son nor offers a glimpse of this earliest-known Shuler generation.

At the outset, the designation “Orphans’ Court” is sufficiently misleading in name and scope to warrant a brief introduction. Derived from the English courts of equity, Orphans’ Courts were tribunals with probate and surrogate jurisdiction convened periodically at varying locations to address matters of non-monetary relief – in this case to settle a question pertaining to land. Francis Shuler, who had died or been killed between August of 1741 and early February of 1742, left no will. Nevertheless, according to son Valentine’s claim, he owned approximately 200 acres of land in Tulpehocken.

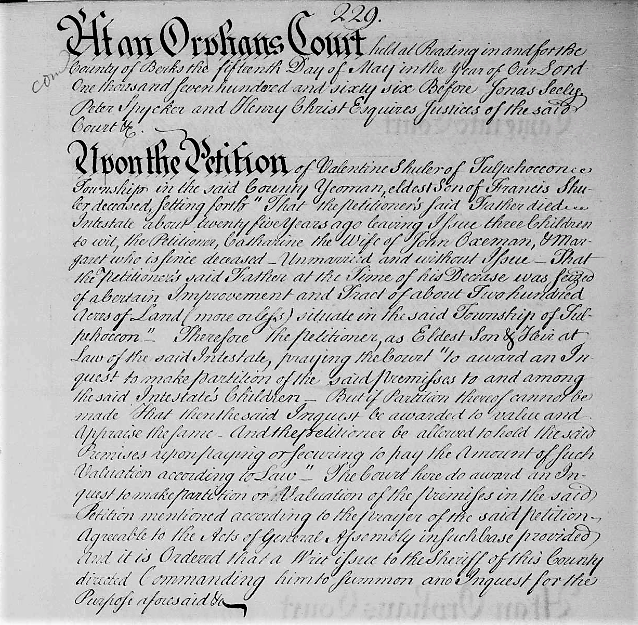

The 1766 Petition

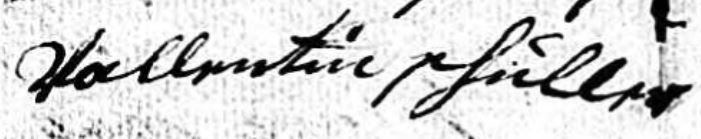

Three Orphans’ Court entries have survived in the Berks County archives. One is the petition itself written in English by a lawyer or clerk and signed in German Kurrent by “Vallentin Schuller” as petitioner. This signature, with its double-l spelling of “Valentin”, matches the signature at the top of the Family Register.

The second is a simple docket entry and the third, reproduced below, records the court’s decision to award a formal review by a 12-man panel known as an inquest.

Transcription of the Petition

Note: “to be seized of” = “owned, possessed”

At an Orphans Court held at Reading in and for the County of Berks the fifteenth Day of May in the year of Our Lord one thousand seven hundred and sixty six Before Jonas Seely, Peter Spycker and Henry Christ Esquires Justices of the said Court, &c.

Upon the Petition of Valentine Shuler of Tulpehoccon Township in the said County, Yeoman, eldest Son of Francis Shuler deceased, setting forth “That the petitioner’s said Father died Intestate about twenty five years ago leaving Issue three Children to wit, the Petitioner, Catherine the Wife of John Oxeman, & Margaret who is since deceased – Unmarried and without Issue – That the Petitioner’s said Father at the Time of Decease was seized of a certain Improvement and Tract of about Two hundred acres of Land (more or less) situate in the said Township of Tulpehoccon” – Therefore the petitioner, as Eldest Son & Heir at Law of the said Intestate, praying the Court “to award an Inquest to make partition of the said premises to and among the said Intestate’s Children – But if Partition thereof cannot be made That then the said Inquest be awarded to value and appraise the same – and the petitioner be allowed to hold the said Premises upon paying or securing to pay the amount of such Valuation according to Law” – The Court here do award an Inquest to make partition or Valuation of the Premises in the said Petition mentioned according to the prayer of the said Petition – agreeable to the Acts of General Assembly in such case provided and it is Ordered that a writ issue to the Sheriff of this County directed Commanding him to summon an Inquest for the Purpose aforesaid, &c.

Sketch of this Generation

This sketch, based on the Petition and the 1742 Estate Papers (see below) as primary sources, shows Valentine Shuler’s place within this generation as petitioner.

Parents

Francis Shuler [“Francis Shuller”]

[born? – d. bet. Aug. 1741 and early Feb. 1742, Bethel Twp., then Lancaster County]

Anna Margred Shuller

[maiden name and dates unknown]

Children

Valentine Shuler [“Vallentin Schuller”]

[b. 1739 or earlier – d. 1812] m. see biography

Catherine [Schullerin]

[b. 1739 or earlier – d. ?] m. John Oxeman

Margaret/Anna Margaretha [Schullerin]

[b. 1 July, bapt. 3 August 1741 (Little Tulpehocken Church); d. bef. 1766, unmarried, without children.]

Land in Tulpehocken

Valentine, whose date of birth, like that of his sister Catherine, is undocumented, was at the youngest 27 years old at the time of the petition and the father of the first two children named in the Schuller Family Register. Accounting for the petition’s late date – 25 years after his father’s death and well after the hostilities of the French and Indian War had ceased – is one of many tasks before us. The petition may have been occasioned at the bidding or demand of his surviving sister, Catherine and husband John Oxeman, by a request of the township or neighboring landholders, by the reorganization of the northern strip of Richard Penn’s Manor of Andolhea in 1765, or, simply, by his own wish to pursue a stale, but rightful, claim.

There are, in fact, two parcels of Shuler land in the petition: the Tulpehocken land said to belong to Francis and, by definition, the Tulpehocken freehold operated by Valentine as “Yeoman” (Scholl 2008: 15). Efforts to locate these parcels and the elusive records of the inquest are ongoing. On the other hand, it is also possible that records will reveal these parcels to have been one and the same.

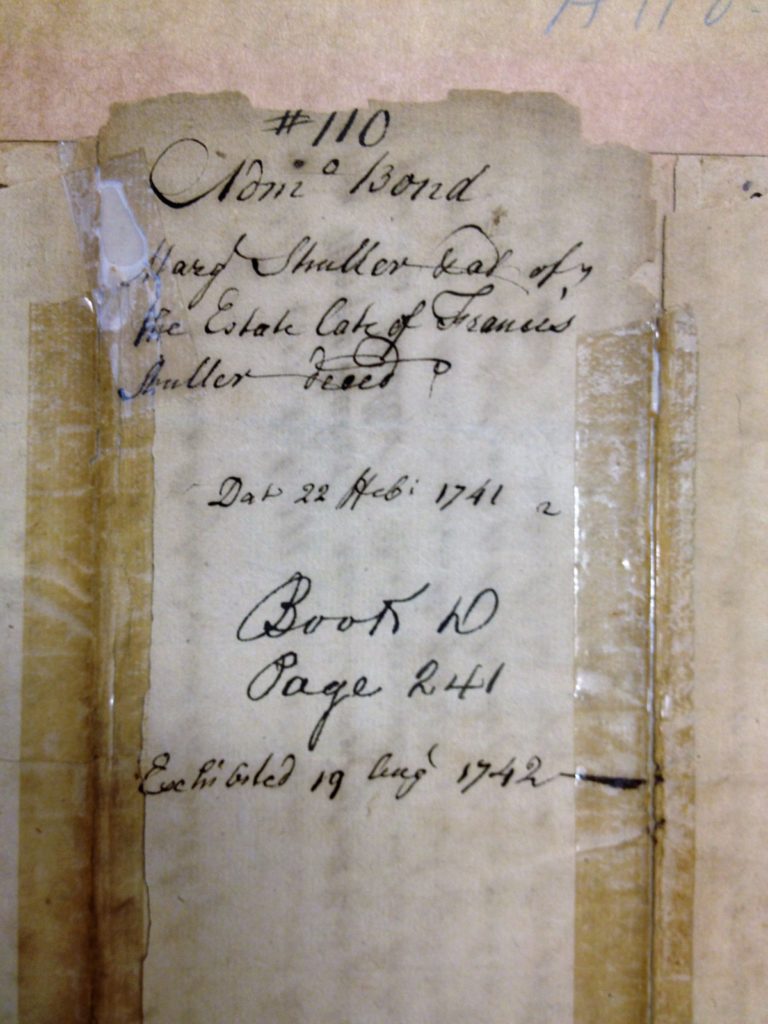

The 1742 (NS) Estate Papers

The year provided by the 1766 petition [1766-25 = 1741] allows us to consider an earlier primary source, the original of which is held in Philadelphia. This is the Administration and Bond of Margt. Shuller et al. of the Estate late of Francis Shuller deceased [Book D, Page 241; City of Philadelphia Archives, Administration No. 110/1741]. In the early days, Lancaster county filings were directed to the Office of the Register General in Philadelphia. Berks county, as should be recalled, was not created until 1752. As legal instruments, “Letters of Administration” authorized heirs and creditors to represent persons who had died intestate. Bonds were posted to assure proper accounting and processing. Although the administration document and its related estate inventory have been digitized and are available online,* we have chosen to feature photographs of the originals. These earliest-known Shuler primary sources are in precarious states of preservation and, contrary to best conservation practices, have been mended in part with transparent tape.

*Pennsylvania, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1683-1993 for Francis Shuller

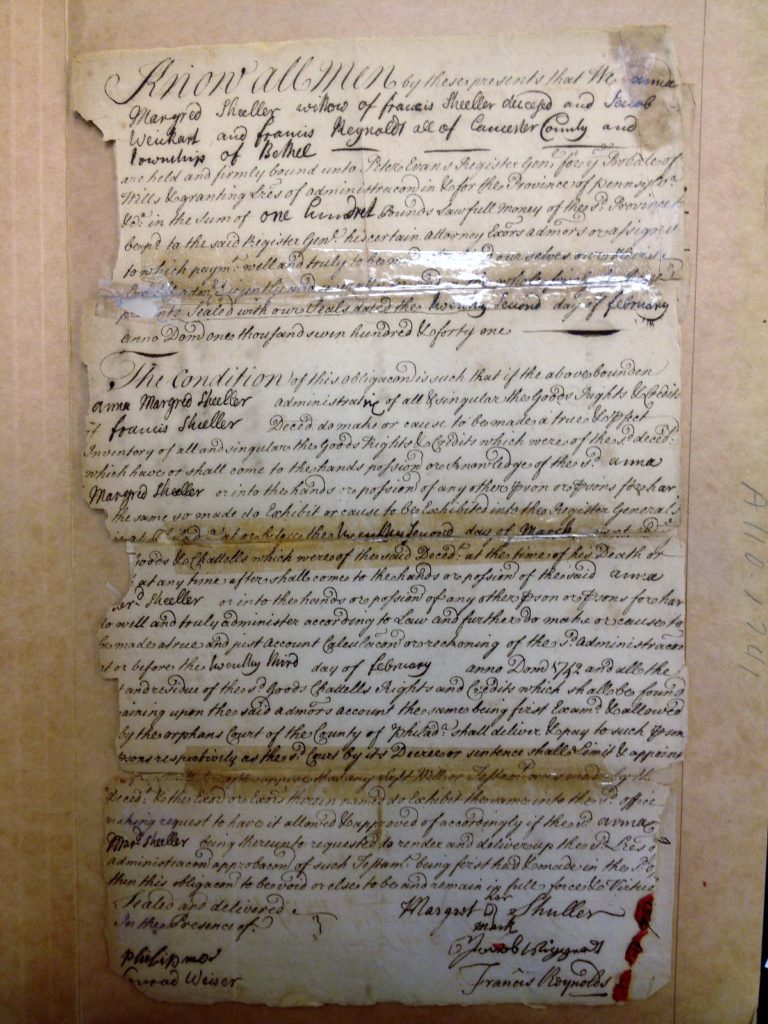

Letters of Administration

Transcription of the Letters of Administration

Note: Gaps in the text have been filled by reference to identical formulations in other Letters of Administration in the same volume. Abbreviations have been removed and spellings modernized.

Know all Men by these presents that We Anna Margred Shuler widow of Francis Shuler deceased and Jacob Weickart and Francis Reynolds all of Lancaster County and township of Bethel – are held and firmly bound unto Peter Evans Register General for the probate of wills and granting Letters of Administration in and for the Province of Pennsylvania etc. in the sum of one hundred pounds lawful money of the said Province to be paid to the said Register General, his certain attorney, executors, administrators or assigns to which payment well and truly to be made We bind ourselves, our Heirs, executors and administrators jointly and severally for and in the whole firmly by these presents sealed with our seals dated the twenty second day of February Anno Domini one thousand seven hundred & forty one.

The Condition of this obligation is such that if the above bounden Anna Margred Shuler administratix of all and singular the goods rights and credits of Francis Shuler deceased do make or cause to be made a true and perfect inventory of all and singular the goods rights and credits which were of the said deceased which have or shall come to the hands possession or knowledge of the said Anna Margred Shuler or into the hands or possession of any other person or persons for her and the same so made do exhibit or cause to be exhibited into the Register General’s Office at Philadelphia at or before the twenty second day of March next and the same goods and chattels which were of the said deceased at the time of his death or which at any time after shall come to the hands or possession of the said Anna Margred Shuler or into the hands or possession of any other person or persons for her, well and truly administer according to law and further do make or cause to be made a true and just account calculation or reckoning of the said administration at or before the twenty third day of February Anno Domini 1742 and all the rest and residue of the said goods chattels rights and credits which shall be found remaining upon the said administrator’s account the same being first examined and allowed of by the Orphans’ Court of the County of Philadelphia shall deliver and pay to such person or persons respectively as the said court by its decree or sentence shall limit and appoint and if it shall hereafter appear that any last will or testament was made by the said deceased and the executor or executors therein named do exhibit the same into the said Office making request to have it allowed and approved of accordingly if the said Anna Margred Shuler being thereunto requested do render and deliver up the said Letters of Administration, approbation of such testament being first had and made in the said Office, then this obligation to be void or else to be and remain in full force and virtue.

Sealed and delivered

In the Presence of

Philip Meir

Conrad Weiser

her

Margret [—–] Shuller

mark

Jacob Wiggerdt

Francis Reynolds

s e a l s

The witnesses at the document’s lower left are Philip Meir (whose ubiquitous surname in its many variants continues to obscure his identity) and the illustrious Conrad Weiser, then serving his first year as magistrate. Francis’s wife, “Anna Margred”, executrix of the estate, was unable to sign her own name. Her shakily written mark is the earliest known tangible point in the family’s history. Jacob Weickert, whose surname is also to be found in various spellings, was a Tulpehocken wheelwright who named his “good friend and countryman” [guter Freund und Landsmann] Conrad Weiser executor of his own 1755 estate. Weickert’s signature as “Wiggerdt” in the Shuler administration papers, and in his own German- and English-language wills,* are identical. He and his wife (whether from the first or second of his two marriages is unknown) are of assumed, but as yet unclear, kinship to Francis and Anna Margred Shuler. Francis Reynolds, on the other hand, was a prominent figure whose relationship to the estate was in all likelihood a financial one as creditor. He is referred to several times in Strouss’s The Founding of Fredericksburg. The location of Reynolds’s own land can be seen at the right-most edge of the map included in Strouss’s essay (Strouss: 104).

*Pennsylvania, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1683-1993 for Jacob Weikert

Timeline

Two calendar systems were in place at the time the Letters of Administration and the related Inventory (see below) were signed and dated. One was the Civil or Legal calendar (also known as the Julian or Old Style/OS calendar) which began on March 25th. The other was the Historical calendar (also known as the Gregorian or New Style/NS calendar) which began on January 1st. The new years these calendar systems generated were out of phase between January 1st and March 24th. Prior to 1752, when the Old Style (OS) calendar was replaced officially by the New Style (NS) calendar in England and its possessions, a dual dating system was often used to rule out ambiguities during the three months of overlap. This can be seen in the Inventory where “1741/2” refers to two years at once. According to the OS calendar, February 19th was still 1741 since the date precedes the new year beginning on March 25th. According to the NS calendar, February 19th was already 1742 since the date follows the new year beginning on January 1st.

At the time Anna Margred signed the Letters of Administration as executrix with her mark on February 22nd, 1742 (NS), she was the mother of two small and suddenly fatherless children and a 7 ½ -month-old infant (the “Valentine”, “Catherine”, and “Margaret” of the 1766 petition). Her anguish, fear and sheer misery on the American frontier are beyond our comprehension. They had already all lived through one of the worst winters in Pennsylvania history as described in Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette (Philadelphia) on April 9th, 1741. Anna Margred was pregnant throughout all of it. “We hear from Lancaster County, that during the Continuance of the great Snow which in general was more than three Foot deep, great Numbers of the back inhabitants suffer’d much for want of Bread; that many families of New-Settlers for some time had little else to subsist them but the Carcases of Deer they found dead or dying in the Swamps or Runns about their Houses; and although they had given all their Grain to their Cattle, many Horses and Cows are dead, and the greatest Part of the Gangs in the Woods are dead; that the Deers which could not struggle through the Snow to the Springs are believed to be all dead, and many of those which did get into the Savannahs are also dead, ten, twelve and fifteen being found in the Compass of a few Acres of Land. The Indians fear the Winter has been so fatal to the Deer, Turkey, &c in these Northern Parts, that they will be scarce for Years.”

Francis Shuler’s three little children grew up without him as father. For us as historian descendants, this death presents the greatest of disruptions and obstacles: whatever Francis Shuler had to pass on to his children in stories, was suddenly lost forever between August 1741 and early February 1742.

The Inventory

Transcription of the Inventory

Note: The inventory is written in an English hand. In the reformatted transcription below, the original spellings have been maintained and in some cases annotated [in square brackets]. The series of question marks ??? does not refer to the preceding term, but rather replaces the term or terms ‘beneath’ that have not yet been deciphered satisfactorily. Valuations are given in pounds, shillings and pence at 12 pence to the shilling and 20 shillings to the pound. The “Wiggerdt” signature is written in German Kurrentschrift; the “Meir” signature appears here in the idiosyncratic English printing of an otherwise German hand.

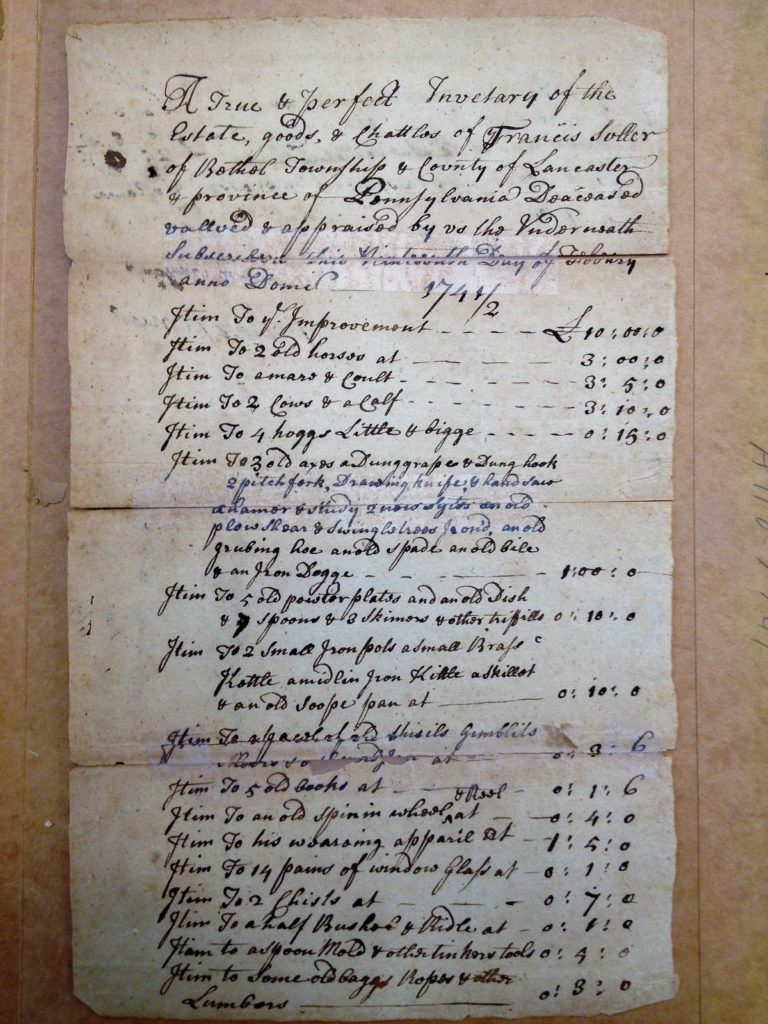

A True & perfect Invetary of the Estate, goods & chattles of Francis Shuler [here “Soller”; on the enveloping versos: “Shuller”] of Bethel Township & County of Lancaster & province of Pennsylvania Deceased vallued & appraised by us the Underneath Subscribed this Nineteenth Day of February anno Domi. 1741/2

To sd Improvement (£10)

To 2 old horses (£3)

To a mare & coult (£3, 5 shillings)

To 2 cows & a calf (£3, 10 shillings)

To 4 hoggs Little & bigge (15 shillings)

——————————————

To 3 old axes a Dunggraper & Dung hook

2 pitchfork, Drawing knife & hand saw

a hamer ??? 2 new Sytes [sythes] an old

plow shear & Swingletrees ??? an old

grubing hoe an old spade an old bile [“Beil”/Spalthammer, Eng. splitting maul]

& an Iron Dogge [skidding tongs, log dog] (£1)

——————————————

To 5 old pewter plates and an old Dish

& 7 spoons & skimers & other triffills (10 shillings)

To 2 small Iron pots a small Brass

Kettle a midlin Iron Kittle a Skillet

& an old Soope pan (10 shillings)

To a ??? of old shisils gimblits [chisels gimlets]

??? (3 shillings, 6 pence)

To 5 old books (1 shilling, 6 pence)

To an old spinnin wheel & stool (4 shillings)

To his weareing apparil (£1, 5 shillings)

To 14 pains of window glass (1 shilling)

To 2 Chists [chests]( 7 shillings)

To a half Bushel and ridle [seive/strainer] (1 shilling)

To a Spoon Mold & other tinkers tools (5 shillings)

To Some old baggs Ropes & other

Lumbers (3 shillings)

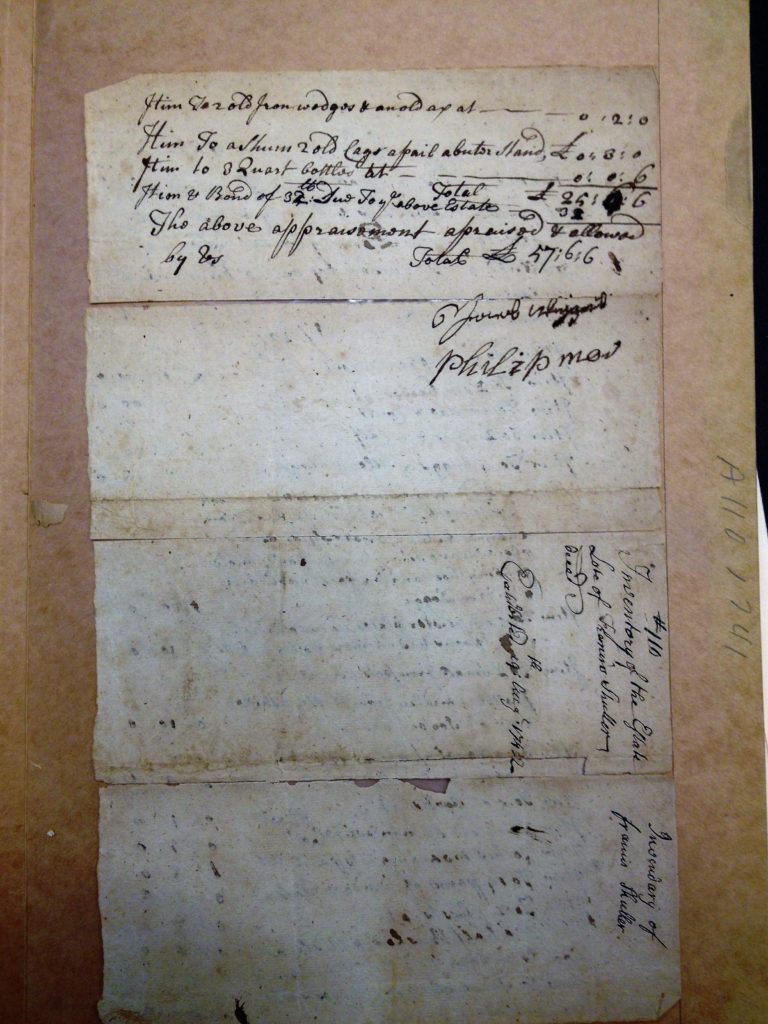

To 2 old Iron wedges & an old ax (2 shillings)

To a Shurn [churn] 2 old Cags [kegs] a pail a buter Stand (3 shillings)

To 3 Quart bottles (6 pence)

Total £25, 6 shillings, 6 pence

Bond of £32 Due To sd above Estate

The above appraisement apraised & allowed

by us Total: £57, 6 shillings, 6 pence

Jacob Wiggerdt

Philip Meir

Verso A:

#110 Inventory of the Estate Late of Francis Shuller decsd

Exhibited 19 Aug. 1742

Verso B:

Invendary of Francis Shuller

Note: dashed lines have been added to the transcription above in order to bring the inventory’s three distinct sections to the fore.

Francis Shuler’s estate inventory takes us on a walk, let’s imagine, from hilltop to hearth. Pasture land and fields below are covered with snow and ice. The Little Swatara is frozen over in the shallows. Inside the small barn, axes, their heads carefully oiled and wrapped, lean against the outer wall atop logs held up out of the mud on blocks. Swingletrees, a splitting maul and skidding tongs hanging from a beam speak of felling trees and clearing the land. The plowshare is as worn as the two old, gaunt horses steaming into the winter air. The mare and colt, the cow and calf, and the hogs have already been led away. We pass the garden. Pumpkins have long frozen into piles of rot under their own weight. Wind from the mountains rustles a patch of maize stalks. We enter the small cabin to count pewter plates and other household items, chests, pieces of clothing, boards and books to be kept dry. Maybe one of the books will come to hold the “Family Register” someday. Iron wedges and an ax are ready to split wood for the fire. But today the fire isn’t burning and there’s no one here. We tend to the two old horses and leave. We’ll come back for them tomorrow. The inventory is finished.

There is nothing in this inventory to indicate a profession or trade beyond small-scale farming and working as a member of the “Gangs in the Woods” mentioned in the Pennsylvania Gazette’s report. The sole luxuries are 14 panes of window glass – until we recall the two scythes. They are new. Were they intended for the weeks after Margaret was born? For later in autumn? There are also many things not on the list. There is no gun, no shot, no gunpowder. Particularly the absence of firearms has the potential to inspire narrative: Francis was killed somewhere in the wilderness and his gun was taken. But matters of narrative differ substantially from matters of evidence – as an inspiringly level-headed study by James Lindgren and Justin Heather reminds. Part of the perpetual discussion of Second Amendment rights, “Counting Guns in Early America” analyzes the significance of the presence or absence of firearms in mid- to late-18th century estate inventories. Such inventories “are far from complete lists of property owned at death” (Lindgren and Heather 2002: 1830) and there are reasons why guns, or anything else for that matter, may not have been recorded – in our case, a table and chairs, a bed, bedding, candles, a wagon and much else. Little Valentine, Catharine, their mother and baby sister are now somewhere else. But where did they go?

Bethel Township

Bethel Township was created out of Lebanon Township. Francis and Anna Margred were not new to the place, the name was new to the place. Reformed minister Johann Philipp Boehm visited the region in 1740 and 1741 NS in search of funds without mention of “Bethel” in his report to the Classis of Amsterdam – writing only of “Schwadare”/”Schwatare” [Swatara] and “Quitenbehelen” [Quittapahilla], seven or eight miles above “Dolpihacken” [Tulpehocken] which, despite their promising Reformed congregations, were places populated “largely by very poor people who are scarcely capable of even taking care of themselves.” [ Folio 89, entry 4 concerning “Dolpihacken”] Nevertheless, as we learn from the same historical manuscript collection [Folio 92], the Swatara Reformed congregation managed to commit itself on the 14th of February 1741 to pay a preacher an annual salary of £5 and 10 bushels of oats. The Quittapahilla congregation had already joined the Tulpehocken congregation three days earlier for a combined salary commitment of £15 and 50 bushels of oats. [Folio 95]

The early locations and names of churches, the identities of congregations, as well as the changing borders of counties and townships present relentless challenges for historical research in Pennsylvania. But whether there or anywhere else, we are always looking for needles in haystacks; finding the right haystack is always the first step. Bethel Township’s borders enclosed a sizeable portion of Lancaster County before Berks County was founded. Surely this map and this map will assist narrowing the search for the land in the Inventory (the “Improvement”). Readers preferring local color over black and white, however, may wish to go straight to the Lancaster Court’s 1739 description (in Rupp 1844: 302) – “That the division line begin at Swatara creek, at a stony ridge, about half a mile below John Tittle’s, and continuing along the said ridge easterly to Tolpehocken township, to the northward of Tobias Pickels, so as to leave John Benaugle, Adam Steel, Thomas Ewersly and Mathias Tise, to the southard of the said line; that the northernmost division be named, and called Bethel – the southern division continue the name Lebanon.” It is fascinating how such ultimately transient measures were endowed with imaginary permanence in a rapidly changing world. Our needle is perhaps in that haystack.

Clues and Kin

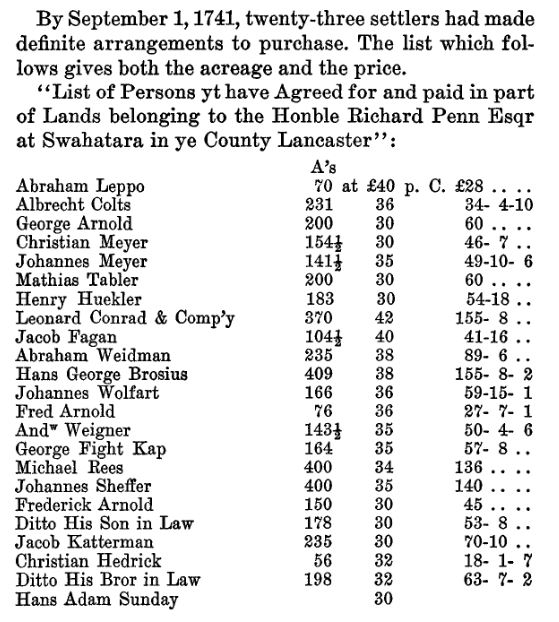

The land in the Inventory’s first line is not the land of Valentine’s 1766 petition. The land in Bethel Township was much smaller. We know this owing to the work of Surveyor General William Parsons in 1741 and the analysis by George Wheeler in the early 1930s. Wheeler’s paper on “Richard Penn’s Manor of Andolhea” is the singularly most important secondary source for our research in this early period – for one reason because it includes a list of 23 settlers, already long in the Swatara Creek region, who, by the 1st of September, 1741, had contracted to purchase land from Richard Penn’s Manor. Many had lived on and worked the land there for nearly a decade before the creation of the manor [in modern terms, a Penn family-owned real estate development] enclosed them within its borders.

The list (Wheeler 1934: 200) has four columns showing the names of purchasers, the total acreage, the price in pounds per 100 acres and the line-by-line totals. As can be seen, the land prices varied from £30 to £42 per hundred acres. The £34 average is over twice that of the conventionally used mid-century Pennsylvania average of £15 ½ . ( Gallo 2019: n.p., at fn. 31)

Using these fortuitous data from the same time and same region, the appraised value of Francis’s land in the Inventory (£10) suggests that it was between 23.8 and 33.3 acres – or, using the £34 average, 29.4 acres – in total area (assuming, of course, that it was comparable in quality to the other parcels). The land in Valentine’s 1766 petition, however, encompassed two-hundred acres “more or less”. This quickly increases the importance of any inquest documents since, besides whatever historical information they may contain, Valentine would have been forced to argue his case without the benefit of supporting evidence. The Tulpehocken property is not listed in his father’s estate inventory.

After the Letters of Administration were filed, minister Johann Caspar Stoever’s records show the marriage of an “Anna Margaretha Schueler” and “John Abraham Leppo” in Swatara on the 22nd of March, 1742 [which we assume to have be an Old-Style calendar date]. We have not yet been able to proof the transcription of the original entry. Leppo’s name is at the top of the list of Andolhea Manor land purchasers. If this is indeed the trace of a remarriage one year and one month after the Letters of Administration were filed, it is not the only appearance of the French Huguenot name “Leppo” [“LeBois”, “Lepo”, “Lebo”] in connection with our Shuler family’s, as well as the Weickert family’s colonial histories.“Margretha Lepo” is named as one of Weickert’s lesser heirs in 1755. Moreover, at the baptism of Valentine Shuler’s first-born daughter “Anna Margaretha” at Christ Church in April of 1761, it was one “Anna Margaretha Leppo” who served as sponsor. The Jacob Weickert who, along with his wife, served as sponsors at this baptism, is undoubtedly the same Jacob Weickert who co-signed Francis Shuler’s estate papers and posted bond.

We welcome any questions and contributions — especially those that are based on primary sources.