FAQs

There is a chance.

From Bethel and Tulpehocken, the family crossed the Blue Mountains to Pine Grove and moved next to Lower Mahanoy Township south of Herndon. Valentine Shuler’s land was situated along Fidler’s Run on both sides of the east-west stretch of today’s State Route 225 at Mandata. In the wake of the difficult dissolution of his father’s estate in 1812, son John Valentine Shuler left his brothers’ and sisters’ families behind and, with his own family, headed to Hopewell Township in Licking County, Ohio. The Ohio land had been acquired by his close friend in Mahanoy, Thomas Dobson (1755-1830).

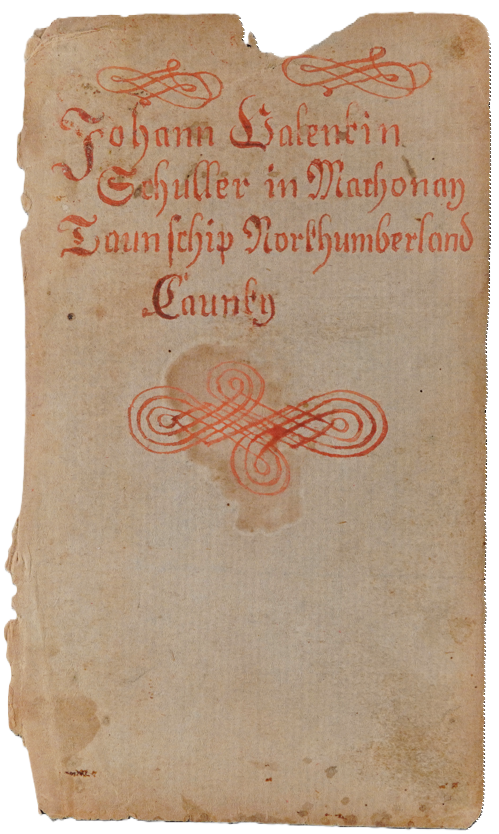

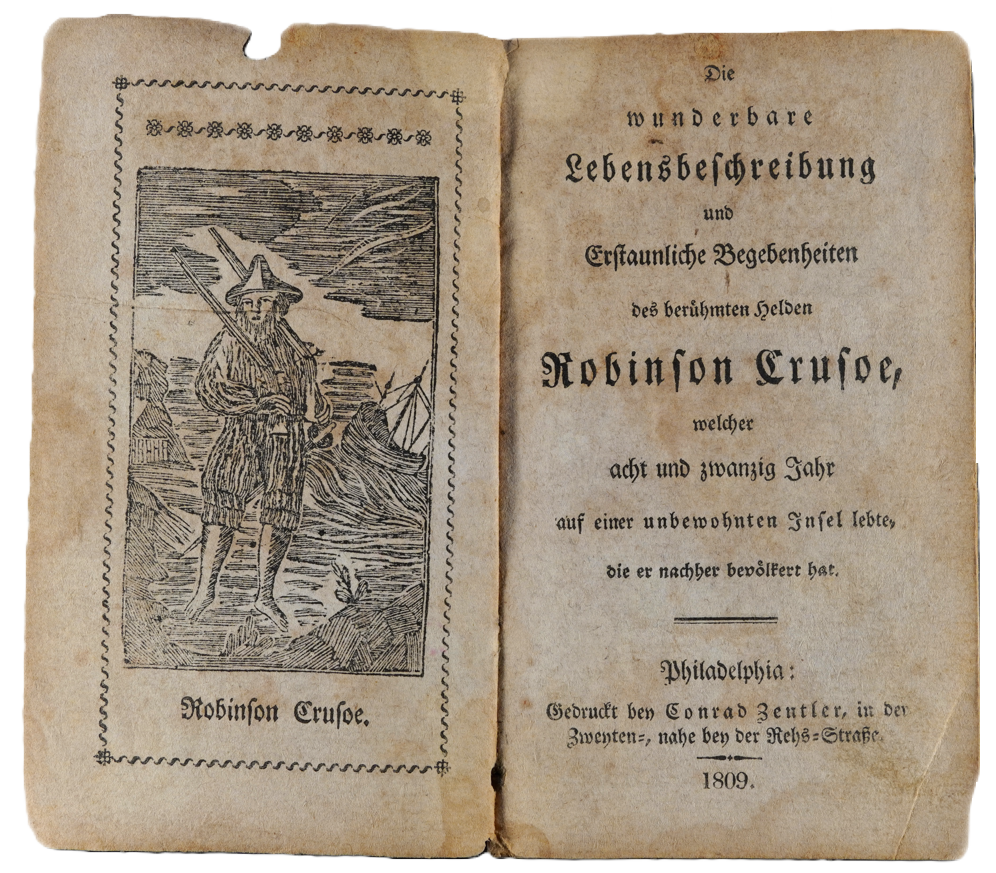

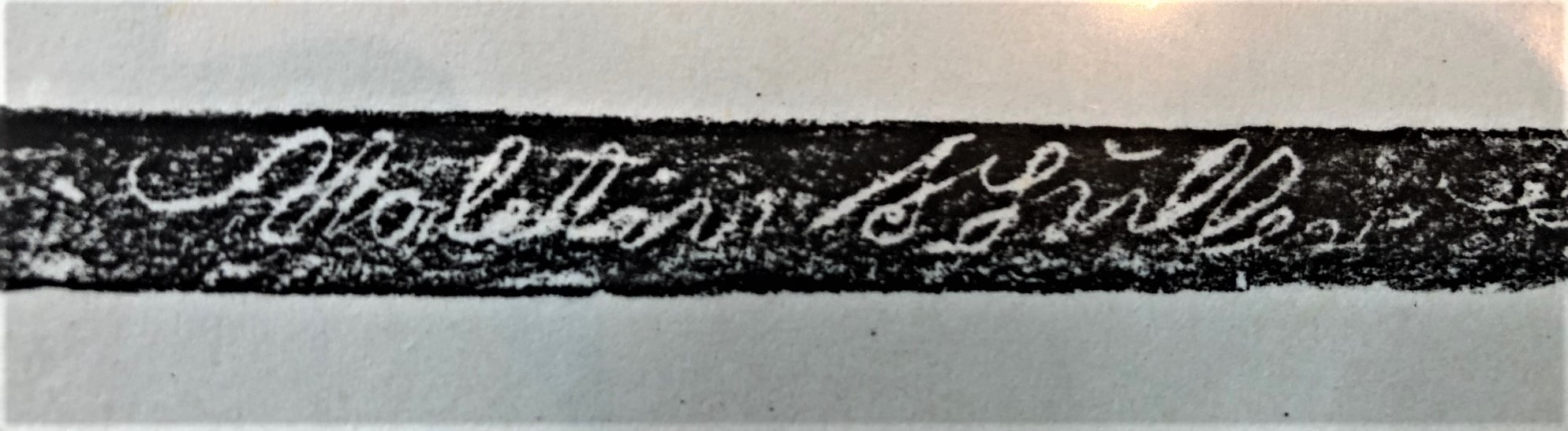

Exlibris by “Johann Valentin Schuller in Machonay Taunschip Northumberland Caunty” lettered in Frakturschrift in an extremely rare, illustrated German edition of The Life of Robinson Crusoe entitled: Die wunderbare Lebensbeschreibung und Erstaunliche Begebenheiten des berühmten Helden Robinson Crusoe, welcher acht und zwanzig Jahr auf einer unbewohnten Insel lebte, die er nachher bevölkert hat. Philadelphia: Conrad Zentler, 1809. 14 x 8 cm., 141 pages. Private collection.

Listed below are the children and grandchildren of Valentine Shuler [“Vallentin Schuller”] whose own name is at the top of The Schuller Family Register. Names are repeated [inside brackets] in the most common variant spellings solely for the benefit of internet search engines since we do not know what form the surname “Schuller” may have taken within the descendant families of “Andreas Schuller” and “Georg Wendell Schuller” in particular. Nor can we know how the names of John Valentine’s descendants may have been recorded elsewhere.

Johann Valentin Schuller [John Valentine Shuler, John Valentine Schuler] m. Eva Barbara Huber. Their children were Johannes, Eva Barbara, Catherine, Daniel, Valentine and William A. Shuler. [Johannes (John) Shuler, Johannes (John) Schuler; Eva Barbara Shuler, Eva Barbara Schuler; Catherine Shuler, Catherine Schuler; Daniel Shuler, Daniel Schuler; Valentine Shuler, Valentine Schuler; and William A. Shuler, William A. Schuler.]

Anna Margred [Anna Maria Margaretha Schullerin] m. Nicholas Eckel.

Catarina [Katharina Schullerin, d. bef. 1812] m. John Smith. The Smith children were Adam Smith, John Smith, Nicholas Smith, Katherine Smith and Elizabeth Smith.

Andreas Schuller [Andrew Shuler, Andrew Schuler, d. in or bef. 1812], whose wife’s name is unknown, was the father of David, Samuel, Joseph, Frederick, Mary and Margaret. [David Shuler, David Schuler; Samuel Shuler, Samuel Schuler; Joseph Shuler, Joseph Schuler; Frederick Shuler, Frederick Schuler; Mary Shuler, Mary Schuler; and Margaret Shuler, Margaret Schuler.]

Sußanna Catharina Schullerin [Susanna Schuller, d. bef. 1812] m. John Hubler. The Hubler children were Michael Hubler, John Hubler, Margaret Hubler, Barbara Hubler and Katherine Hubler.

Of Georg Wendel Schuller [George W. Shuler, George W. Schuler, George Shuler, George Schuler] little is known beyond his date of birth and the fact that he was one of the four children living at the time the 1812 estate was processed.

Christina Schullerin [Christina Schuller, Christina Shuler] was Valentine Shuler’s daughter from his exceptionally unhappy marriage to Magdalena Neufang. Whether Christina married at some time after 1812 is unknown.

With the exception of John Valentine Shuler’s family, the information published here stems exclusively from The Schuller Family Register and the 1812 Northumberland County Estate Papers of Valentine Shuler.

This overview will be revised, supplemented and updated whenever primary sources are brought to our attention.

Except for official records, transcripts and certifications, such civil documents as wills and estate inventories, as well as church records that are also available in facsimile, primary sources for our purposes are authentic, untranscribed and untranslated historical documents or unexamined historical objects which provide data for interpretation. They all require proper handling, conservation and storage. Our reliance and insistence upon primary sources are measures to counteract the erroneous information that continues to be promulgated about the history of our family on the internet.

Books with bookplates/exlibris, broadsides, deeds, diaries, drawings, envelopes, family registers, herbals, inscriptions, ledgers, legal documents, letters, maps, Taufscheine [birth and baptismal certificates] as well as bits and pieces of every kind are of immeasurable value to our research – especially because we may be able to glean things from them that others may not.

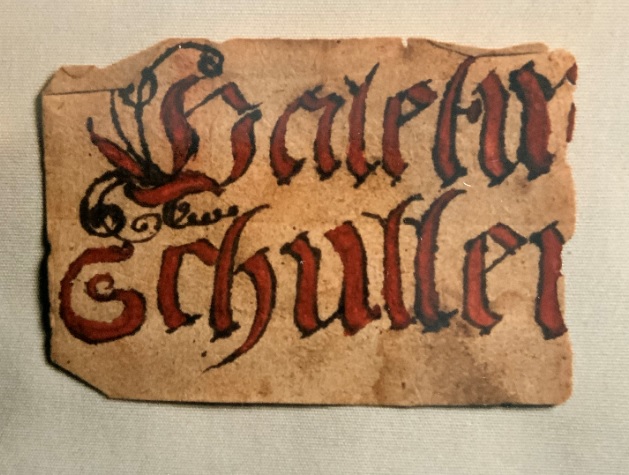

Fragment lettered in Frakturschrift showing the name “Valetin Schuller” with an ornamented initial. Private collection.

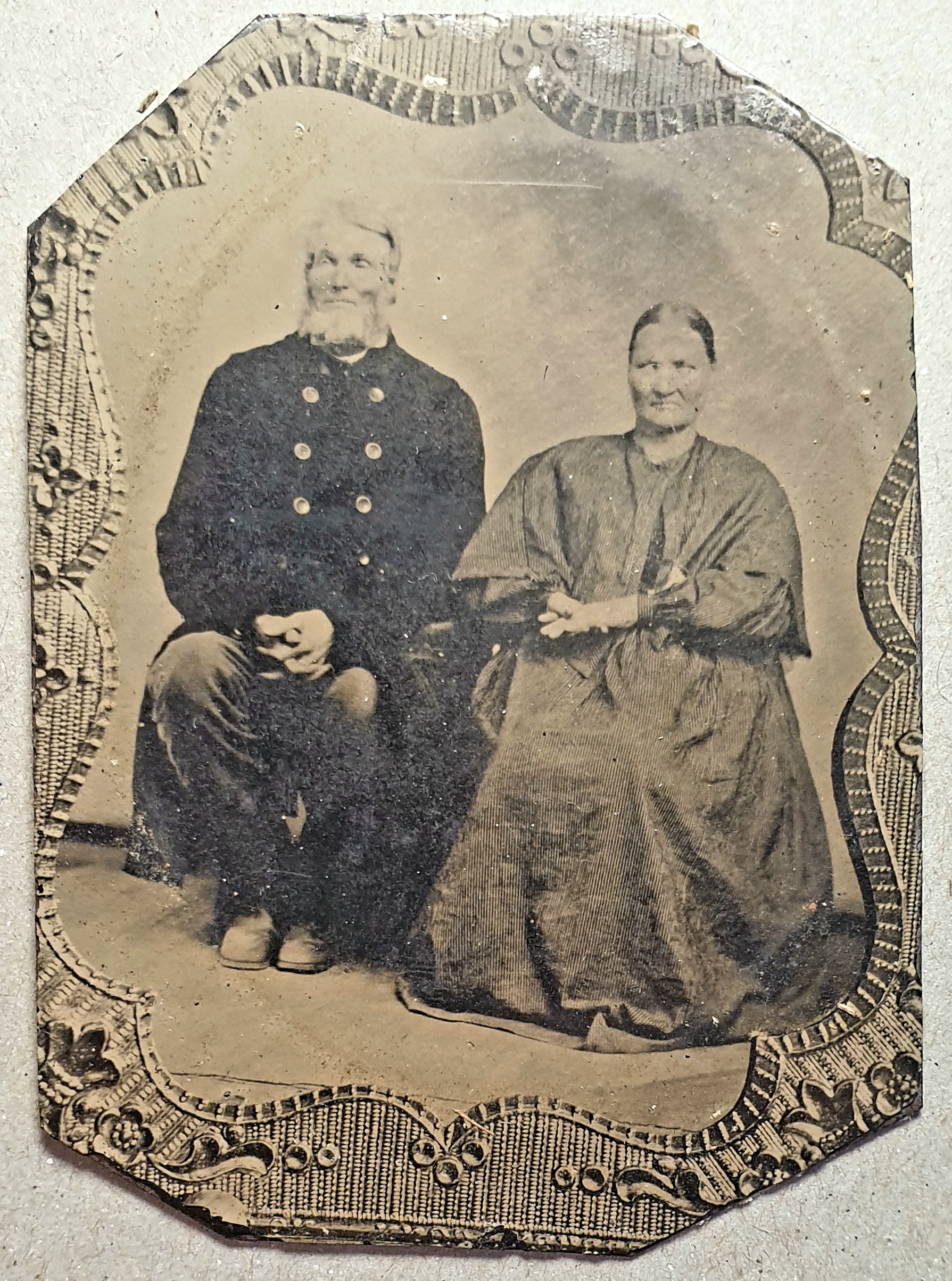

Daguerreotypes, ambrotypes, tintypes [ferrotypes] and other early photographs are of interest provided they show persons who were born prior to the year 1820 as is the case with the portrait of Valentine Shuler (1808-1885) and wife Jane Wills below. This Valentine Shuler was one of John Valentine Shuler’s four sons.

Valentine Shuler (1808-1885) and wife Jane Wills. Jamesport, Missouri, ca. 1875, with passe-partout removed. Plate: 48 x 67 mm. Condition: unrestored. Private collection.

Conservation specialists at local historical societies, museums and university library special collections/rare book departments are usually willing to advise on care and treatment. The U. S. National Archives website features a dedicated section on How to Preserve Family Archives (papers and photographs) and companies such as University Products in Holyoke, MA, are specialized in conservation, storage, display and emergency response supplies for institutional as well as private use.

It is likely that Shuler painted chests, furniture, firearms, silver- and other metal work will be discovered in descendant family collections. Here the current edition of the Metropolitan Museum of Art publication The Care and Handling of Art Objects is a helpful and free guide which can be downloaded as a pdf.

Frottage of a “Valetin Schuller” signature engraved on a rifle muzzle. The spelling “Valetin” is the same as appears in the Fraktur fragment above. The owner of this muzzle is asked to please contact us.

Submitting photographs and scans

If you would like to submit photographs of objects, or high-resolution scans of documents or other works on paper for research purposes, please contact us for details. Your inquiry and submissions will be treated in strict confidence. Transcription, translation and publication of your materials can only be discussed on a case-by-case basis.

Oral history

We do not underestimate the power of oral history and family tradition. If these have the potential of taking us back into early colonial times, please contact us.

It is impossible to work with German primary sources without being able to read the cursive handwriting of everyday called Kurrentschrift [‘Kurrent’ for short] and the Frakturschrift of formal lettering and typefaces [called ‘Fraktur’, blackletter or ‘Gothic’]. Use of these traditional scripts, which have histories stretching back to the middle ages, was ended by decree in the Nazi era in a baffling blend of antisemitism and modernization in 1941. [See the ‘Antiqua-Fraktur Dispute‘.] In colonial America, on the other hand, they were supplanted organically by the dominance of William Penn’s mother tongue. Today, few people on either side of the Atlantic can read Kurrent. This simple fact has serious consequences: transcriptions from original sources are often incorrect.

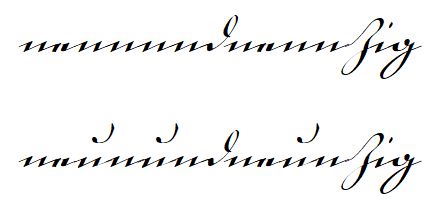

In Fraktur, the name “Johann Valentin Schuller” appears as it does below in red.

In Kurrent, the name appears as it does above in black.

The letter “u” (which is a bit dear to our hearts) has a special form only in German Kurrentschrift. It is written with a small crook above the letter. This distinguishes it from other letters written in similar up-down-up-down strokes of the quill. As an example, here is the number “neunundneunzig” [ninety-nine] first written incorrectly and then correctly:

The crook above the “u” has many forms. Sometimes the stroke is left-right, sometimes right-left, sometimes it looks like a lost comma, sometimes it takes on the form of a floating question mark without the dot — but in all cases it is not the letter “u” with two dots or short parallel strokes above it known as an Umlaut. Such a diacritic changes the sound of the vowels “a”, “o” and “u” to “ä”, “ö” and “ü”. English speakers yearning to experience the difference between “u” and “ü” might begin — inhale! — by rounding their lips as though preparing to pronounce the sound ‘oo’ of “cool” — hold it! — but then say the ‘ee’ of “see” instead: üüüüüüü!

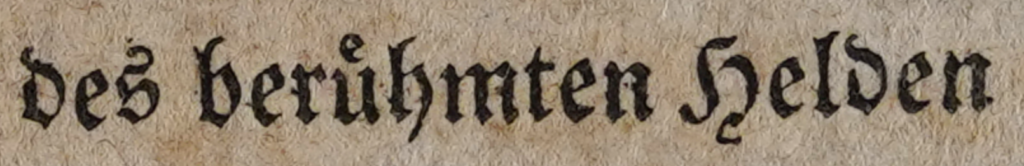

In certain Fraktur typefaces the Umlaut sign appears as a tiny letter “e” above these three vowels, as is the case in the word “berühmt” [‘famous’] in the phrase “des berühmten Helden” [‘of the famous hero’] on the title page of The Life of Robinson Crusoe shown in facsimile in FAQ number one.

The names “Schüller” and “Schüler” have been ruled out of the history of our family’s surname for phonological reasons; the anomalous anglicization as “Sheeler” stems from misreading the letter “u” written with loops in English sources rather than as an approximation of the sound “ü”.

From time to time one also encounters a flat line written above the consonants ‘m’ and ‘n’. This is a doubling sign that ‘doubles’ the consonant below it. In The Schuller Family Register, however, the name “Johann” is written as “Johan” without a macron above the ‘n’. All handwriting has its quirks.

Finally, in both Kurrent and Fraktur, the surnames of women featured the now archaic feminine suffix “-in” [“Schullerin”].

Obviously, the examples above are computer-generated. To view the work of Pennsylvania German folk calligraphers, visit the Free Library of Philadelphia’s collection of 116 “Vorschriften” online and see the many publications of our friends at rdearnestassociates.com/store. We take up the subject in detail in the Johann Valentin Schuller biography (forthcoming)

The surname “Schuyler” (pronounced “Shuler”) offers a challenging case. Although it is widely perceived to be Dutch, it is in fact a form of the ‘German’ surname modified with Anglo-Dutch pronunciation approximations as “Skyler”. Even the famous Schuyler family of American history finds its name’s origins in a German version of the name from the Reformed (Calvinist) city of Emden in East Frisia – in today’s Lower Saxony. See, for example, Kees Kuiken’s biographical portrait of Alida Schuyler (1656-1727), the daughter of Philip Pietersz. Schuyler, on the Huygens Instituut’s Biografisch Portaal van Nederland. [Linked in the bibliography.]

Referring to a small sampling of “The Philadelphia Schuylers” in 1879, George Washington Schuyler reported on a number of German families “spelling their name in the same way as ours, but pronouncing it Shuler.” (Colonial New York: Philip Schuyler and His Family. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1885, vol. 2, 495-496.) There are still people in North America who do the same.

The development of dialects and languages did not stop at historical political or administrative borders. Looking back at the 17th and 18th centuries, the distinction between what we call Dutch and German today is very blurred. The “y” of “Schuyler” once functioned only to make the vowel before it long [elongation/Dehnung] and not as part of the Dutch diphthongs “uy”, “ui”, or “uij”. George Washington Schuyler had chanced upon an interesting historical remnant. But this is not the place to embark on an elaborate linguistic discourse on the development of Dutch and German (or, in the parlance of our example below, the differences between ‘High German’ and ‘Low German’). Instead, we will follow one very concrete example of the name’s historical evolution.

Rev. Johannes Schuyler

Johannes Schuyler was a Reformed minister at Schoharie, New York, and pastor of the Reformed Church at Stone Arabia from 1739 to 1750. It is said that he was born in the German Duchy of Nassau in 1710.

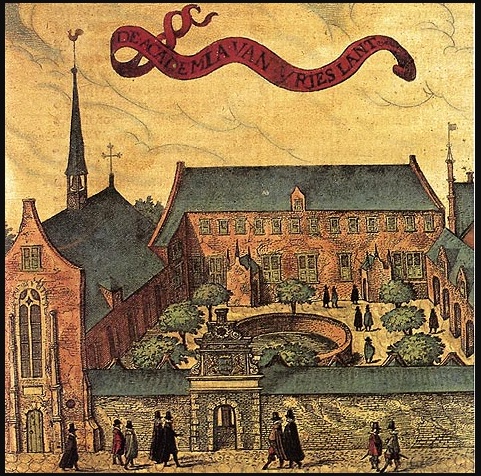

The Academiae Franekerensis, Pieter Feddes van Harlingen (1586-ca.1623).

The Academiae Franekerensis, Pieter Feddes van Harlingen (1586-ca.1623).

In the registers of the University of Friesland in Franeker, the Netherlands [the Academiae Franekerensis], Schuyler appears in the year 1735 as “Johannis Paulus Schulerus, Palatinus”, a student of the Reformed Theologian Hermann Venema (1697-1787), then Rector: “Anno 1735, Hermanno Venema, Rectore Magnifico, nomina sua professi sunt Johannes Paulus Schulerus, Palatinus.” (Album studiosorum academiae Franekerensis. Franeker: T. Wever, 1968, 334). The transformation begins by first latinizing his German name, “Johannes Paul Schuler” as “Johannes Paulus Schulerus” and adding a place of origin — “Palatinus” — in a fashionable academic practice with roots in the Renaissance. Johannes Schuler, in short, was a German student from the Palatinate studying at one of the leading universities for Reformed [Calvinist] Theology. The German Reformed Herborn Academy [the Academia Nassauensis, which would have been much closer to home] did not offer higher academic degrees.

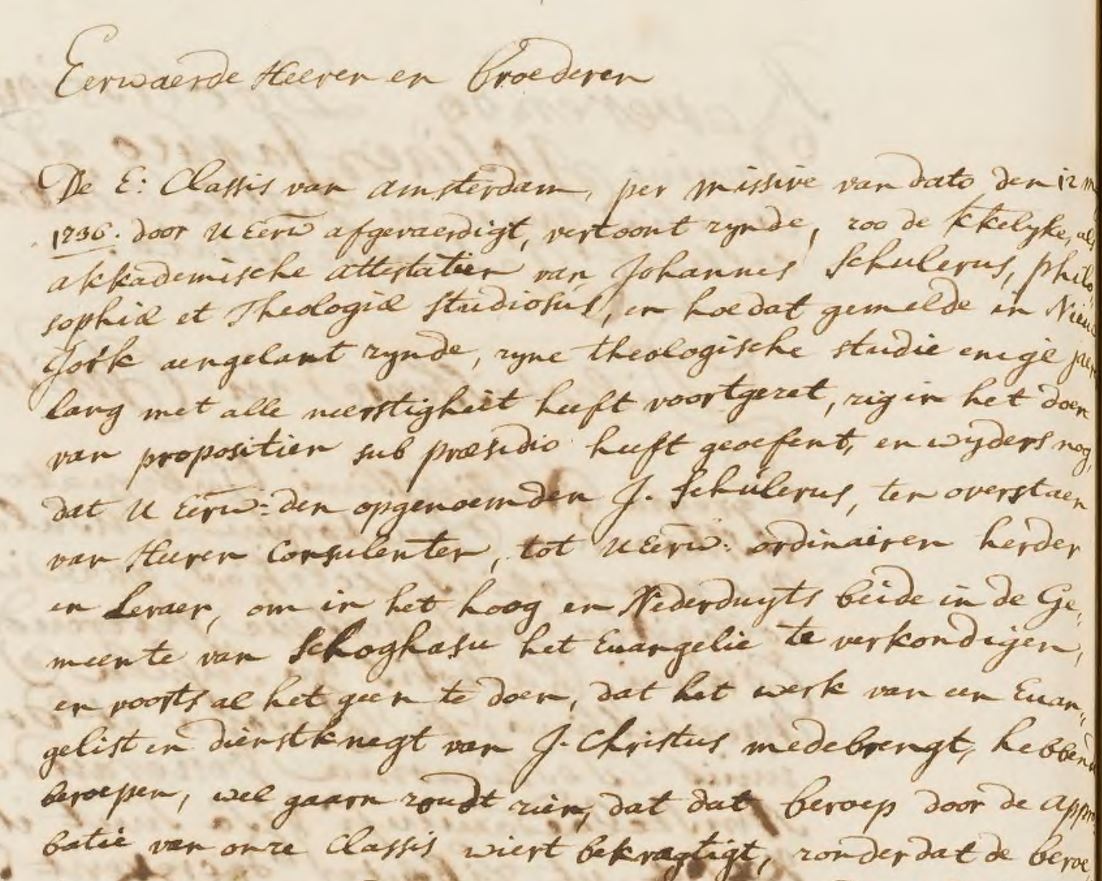

In the transatlantic correspondence dating from 1736 between the Classis of Amsterdam and the Schoharie Consistory pertinent to the call, examination and 1738 ordination of “Johannes Schulerus” at the Belleville Dutch Reformed Church in Essex County, New Jersey, the German surname “Schuler” has become “Schuyler” by way of its latinized version. The excerpt from the Dutch correspondence reproduced below attests to the reverend’s qualifications and ability to preach the Gospel in his native German as well as in Dutch for the Reformed congregation of Schoharie: “…om in het Hoog en Nederduyts beide in de Gemeente van Schogharie het Evangelie te verkondigen …”. The excerpts below stem from records of the Classis of Amsterdam held in the Stadtsarchief Amsterdam.

Classis of Amsterdam to the Schoharie Consistory (12 Oct. 1736). The name “Johannes Schulerus” can be seen in line 3. For the full document, click here.

Classis of Amsterdam to the Schoharie Consistory (12 Oct. 1736). The name “Johannes Schulerus” can be seen in line 3. For the full document, click here.

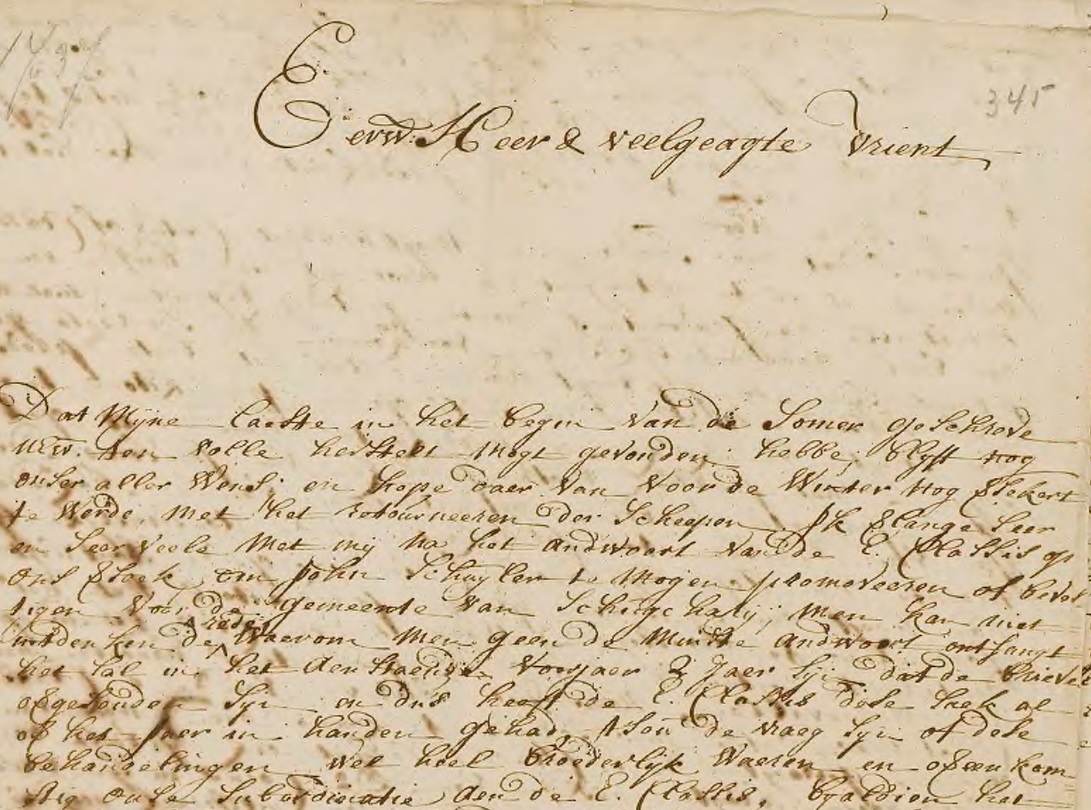

Schoharie Consistory to the Classis of Amsterdam (23 Sept. 1737). The transformation to “John Schuyler” can be seen in line 6. For the full document, click here.

Schoharie Consistory to the Classis of Amsterdam (23 Sept. 1737). The transformation to “John Schuyler” can be seen in line 6. For the full document, click here.

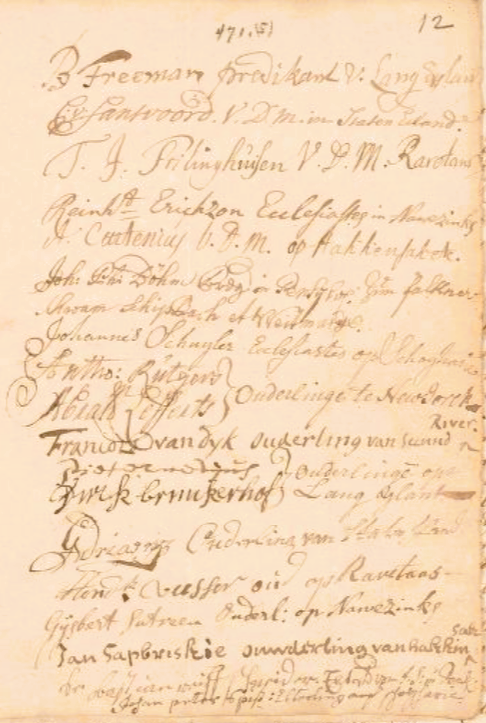

Rev. Schuyler’s own signature can be seen very clearly in another Dutch document below which in this case concerns the formation of a German Reformed Consistory in Pennsylvania (27 Apr. 1738) – folio 12, line 8.

The signature reads “Johannes Schuyler Ecclesiastes op Schogharie”. The entry above it (lines 6 and 7) reads “Joh: Phi Böhm Prdg in Pensylv. Zum Falkner-Schwam Schipbach et Weitmarsche”. This is the famous German Reformed “Preacher” [Prdg = Prediger] Johann Philipp Boehm [Böhm] of Falkner Swamp, Skippack, Whitemarsh and elsewhere in Pennsylvania who visited Swatara and Tulpehocken in our Francis Shuler’s lifetime. [See the description of Bethel in Francis Shuler’s biography.]

Rev. Johann Philipp Boehm [Böhm] and Gabriel Shuler

Boehm, a lay preacher who himself was not ordained until 1729, founded three German Reformed congregations in Pennsylvania in the mid 1720s. One “Gabriel Shuler”, a very early Philadelphia-area settler, whose surname variants (including “Schuller”) in the historical record are more than you can shake the proverbial stick at, was a leading member of Boehm’s Skippack Congregation and one of the delegates sent from Pennsylvania to New York for Boehm’s own ordination. This was years before the future Reverend Johannes Schuyler had arrived in America.

Boehm’s ordination had achieved the support of the Classis of Amsterdam as the governing body administrating the German Reformed Church in colonial America [via the Consistory of the Dutch Reformed Church in New York]. Gabriel Shuler, Fredrick Antes of Falkner Swamp and William De Wees of Whitemarsh “appeared with Boehm before the Dutch ministers in New York, November 18, 1729. The letter of the Classis was duly considered. Boehm and his delegates declared their adherence to the Heidelberg Catechism and the Formulas of Unity. They promised to maintain correspondence with the Classis and to exert themselves to secure the regular payment of Boehm’s salary.” (Hinke, The Life and Letters of the Rev. John Philip Boehm, p. 35. See also pp. 25 and 60.)

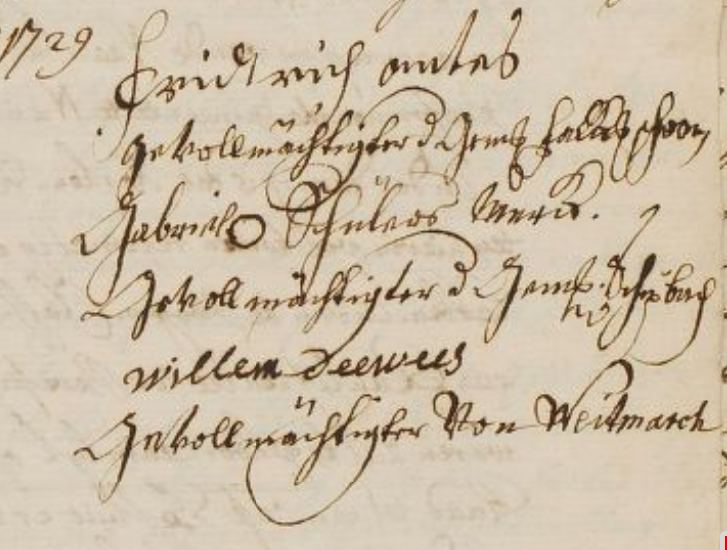

The signatures of “Fridrich Antes”, Gabriel Shuler [see below] and “Willem Dewees”. New York, 18 November 1729. For the full document describing the laying on of hands at Boehm’s New York ordination, click here.

Gabriel Shuler apparently could not write. Line 3 reads: “Gabriel [circle] Schülers Merck” [Gabriel Schüler’s mark].

In view of this inability to write, asking the question how Gabriel’s surname was originally written can only be answered with the remark: ‘that depends upon who wrote it’. It is in view of such realities and such cases as Rev. Johannes Schuyler’s that we continue to consider a wide range of name possibilities as we push back in time beyond our primary-source anchor point of the year 1742.

Large collections of original documents pertinent to 17th and 18th century New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania and elsewhere are in Amsterdam and The Hague. Substantial numbers were consulted by William J. Hinke, our patron saint, in preparing his monumental A History of the Goshenhoppen Reformed Charge and countless other publications. Some of these documents were revisited and others studied for the first time in the course of our own research in the Netherlands. Today many have been digitized and are available online.

Finally, if your family name is “Schuyler” and you pronounce it “Shuler”, please contact us.

In 1687, the year in which the map reproduced below was printed in London, William Penn had already been creating manors and selling land from the Delaware River to Brandywine Creek for five years. The lands of the Swatara and Tulpehocken Creek valleys lay far beyond the elusive western border of Chester County – one of Pennsylvania’s three original counties. Exploration and settlement by Europeans was underway there well before Lancaster County was created in 1729.

A mapp of ye [pronounced “the”] improved part of Pensilvania in America, divided into countyes, townships, and lotts (London, 1687). To download a high-resolution image of the full map from the Library of Congress, click here.

In the conventional narrative, European settlement of the Swatara and Tulpehocken valleys begins in the spring of 1723 when a small group of German families from the thousands sent to the Hudson valley by the English Crown to produce naval stores [pitch, hemp for rope, lumber and other materials] sets off on a final exodus – this time from the headwaters of the Susquehanna. The first had taken them down the Rhine to Rotterdam, from Rotterdam to London and from London to New York. They put in somewhere west of Schoharie and south of Otsego Lake on a journey that is nothing short of dizzying even when retraced on a map with a pencil. Their story had already been told so often by the year 1913 that B. Morris Strouss seemed determined to get it all out in one single breath in a paper read before the Lebanon Historical Society on August 15th that year: “Why they left their homes in the Palatinate and came to London in 1708 and 1709; and how and why they with 3,000 others thence embarked on Dec. 25th 1709, for the province of New York, and how they settled along the Hudson; and how they, because of unjust treatment by the English Colonial authorities, abandoned their homes, and penetrating into the wilderness, settled at Schoharie west of Albany, and how they, because of further and worse persecutions, determined to forsake their new homes which they had conquered from the wild rather than submit to being robbed of their ten years of toil, and migrating south to the Province of Penn’a, settled along the banks of the Swatara and the Tulpehocken, of whose fair and fertile fields they had heard, again to make new homes and be free, is an old story and need not be repeated here in detail.” (Strouss 1913: 100).

Phew! And we agree. Philip Otterness captures the significance of the Schoharie Germans and their Swatara and Tulpehocken settlements quite succinctly in Becoming German: The 1709 Palatine Migration to New York: “Unlike other European settlers in Pennsylvania, the Schoharie Germans approached their new settlement from the west rather than the east, moving through Indian lands. […] their new community was not tethered to Philadelphia but, like the Schoharie settlement, hung suspended between European and Indian worlds.” (Otterness 2004: 139)

German settlements as a buffer zone

Governor William Keith (1669-1749) brought this first group of German settlers from New York to the Tulpehocken Creek valley secretly in order to create a buffer zone between Indians and the English. By permitting them to settle “without the necessary warrants […],” as Barbara Bingham Munger points out, “the stage had been set for land ownership simply by settlement and improvement.” (Munger 1991: 68, 8) Five years earlier, on the 17th of September 1718, Sassoonan (1675-1745), Sachem of the Leni Lenape, and his delegation had released to William Penn and heirs in Philadelphia “all the said Lands, situate between the said two rivers of Delaware and Susquehannah, from Duck-Creek to the Mountains on this Side [of] Lechay [Lehigh].” (Historical Register, 263) But, as Sassoonan argued ten years later, Tulpehocken lay outside that territory.

Below is an excerpt from the Historical Register (London). The “Mr. Logan” with whose name it begins is James Logan (1674-1751), William Penn’s Secretary for Proprietary Affairs and, privately, a well-positioned land speculator. The text features the old letter long-s with which ſome readers might not be ſo accuſtomed.

“West Indies, Pensylvania” in The Historical Register (London, 1728), 264. To read the entire report, click here. It runs from page 249 to 271.

The Penn Manors

Throughout the negotiations, which led ultimately to the displacement of the Leni Lenape, the lands of Tulpehocken continued to refer to a diffuse area west/northwest of Reading. This changed after the new Treaty of 1728 and the creation of both the original Lancaster county and the district of Tulpehocken in 1729. Of the four manors [Penn family ‘real estate developments’] afterwards warranted and surveyed, two are of particular interest. These are Freame’s Manor [after William Penn’s daughter Margaret, wife of Thomas Freame] and Richard Penn’s Manor of Andolhea – [an ancient place name discussed in George Wheeler’s essay on “Richard Penn’s Manor of Andolhea”]. Both were warranted and surveyed in 1732/33 and both were touched or traversed by the Little Swatara. The manors did not come first and then settlement, but rather the perimeters of the manors suddenly surrounded the dwellings and farmlands of European squatters who had assumed ownership based upon enclosure, occupation and improvement. For a detailed and critical discussion of this historical moment, see Francis Jennings’s essay “Incident at Tulpehocken” (1968).

The focus of our current research

Although we have established our family’s connection with Bethel Township and Tulpehocken prior to 1742, there is no evidence to suggest a connection with the Schoharie Germans. Our research is currently focused on the very early (perhaps even pre-1700) arrivals of German Reformed [Calvinists] and onward migrations.

We do not know.

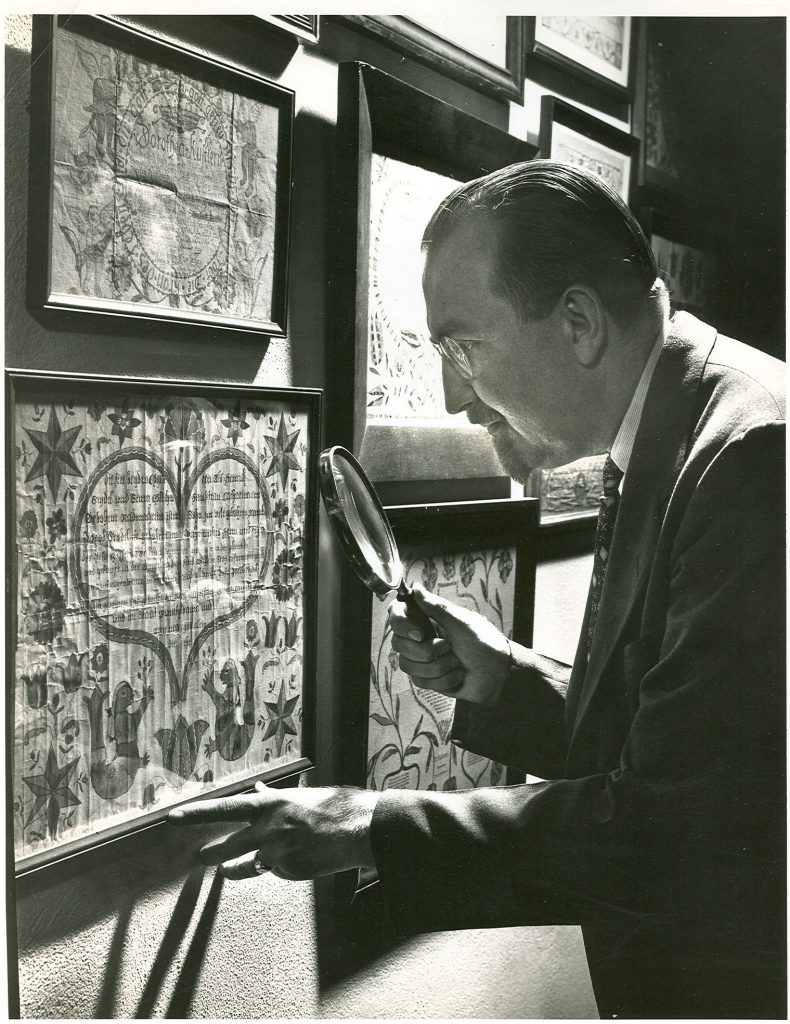

The names “Frantz Schuller” and “Maria Schuler” heading the captain’s list and related lists of Signers of Oaths of Allegiance and Abjuration for the Richard and Elizabeth have been the source of much speculation. The late Alfred L. Shoemaker, Professsor of Linguistics at Franklin and Marshall College, was the first to postulate this “Frantz Schuller” as our family’s immigrant ancestor in his article “Johann Valentin Schüller – Fractur Artist and Author”, published in the long defunct The Pennsylvania Dutchman (Lancaster, October 15, 1951). Notwithstanding its groundbreaking significance and the importance of his work, Shoemaker misspelled the name “Schuller”, filled gaps by supposition and skirted substantial problems that have been compounded in the age of push-button ‘research’ on the internet.

Alfred L. Shoemaker, the Sherlock Holmes of Pennsylvania German folklore, examining a Taufschein by the I.T.W. Fraktur-artist of Berks, County. Photograph: Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Folklife Society Collection at Ursinus College, Collegeville, PA.

There is, after all, no evidence whatsoever that this “Frantz Schuller” is the same person as the “Francis Shuller” whose trail we pick up in the Swatara valley and whose biography is published here. Moreover, as noted elsewhere, the probability is low enough to warrant rigorous reconsideration.

Only a fraction of early ship manifests have survived

There is no exhaustive compilation of passenger lists to colonial America. For substantial periods of time, no passenger lists were maintained at all – not even when ship captains were ordered to do so, as they were by Governor Keith in 1717, acting then in alarm about the “great numbers of foreigners, from Germany, strangers to our language and Constitution” who had already arrived in the Province of Pennsylvania by way of Britain without any administrative surveillance. Yet with the exception of the captains of only three ships that arrived that same year, “the order of the Council was apparently forgotten or failed to be enforced. At least there are no more references in the minutes of the Council to this subject, which implies that during the next ten years no other captains were required to submit lists.” (William J. Hinke, Introduction to Strassburger 1934: vol. 1, xvii – xviii)

Our family’s immigrant Shuler ancestor, whatever his name, could have arrived during the ten-year gap in the Philadelphia lists between 1717 and 1727 or before 1717 when no Philadelphia lists were kept.

He may also have arrived in much earlier times via any number of routes to ports other than Philadelphia. “In none of the other ports of the American colonies, through which German settlers entered, were such lists prepared or preserved. Thousands of Germans came to America through the ports of Boston, New York, Baltimore, Charleston and Savannah. Thus, for example, all the early German Reformed missionaries, sent to Pennsylvania by the Church of Holland, came by way of New York. The same is true of the Lutheran missionaries, who were sent from Halle, Germany. But whatever settlers came through these other ports, their names are lost, at least in the large majority of cases, because no record was kept of them at the time of arrival. In Philadelphia alone did the authorities insist on the preparation of careful and detailed lists of arrivals [as of 1727].” (Hinke, Introduction to Strassburger 1934: vol. 1, xiii)

To these must be added at the very least those lists included as appendices in Knittle’s Early Eighteenth Century Palatine Emigration (242-320) and the 2-volume The Palatine Families of New York: A Study of the German Immigrants who Arrived in Colonial New York in 1710 by Henry Z. Jones. Universal City, CA: Henry Z Jones, 1985.

The recording order on passenger lists

Over the years, scholars in Pennsylvania have reminded of the significance Hinke ascribed to the order of names on the passenger lists. “In many cases the Palatines came over in colonies,” Hinke observed, “with their leader at the head of the list.” (xli) In view of such a role, it is all the more puzzling that no “Schuller” children are listed. The children of other passengers, however, are listed. “Frantz Schuller’s” age is given as 44 and that of “Maria Schuler” as 47 – unlikely ages to begin a family in colonial America were they indeed husband and wife, rather than brother and sister or of other unknown kinship.

Round trip on the same Clymer ship 1733?

If, on the other hand, the „Frantz Schuller“ of the 1733 arrival is indeed one and the same with our “Francis Shuller” whose kinship is unquestionable, there is still no reason to assume that he was our family’s immigrant ancestor since the 1733 arrival could well have been a re-arrival. It is easy to forget that transatlantic crossings were not always one-way, one-time events.

Consider the possibility that there was once a Frantz Schuller already in the colonies by birth or untraceable early arrival. Surprisingly enough, he could have sailed from Philadelphia to Europe in 1733 and returned the same year on the same ship. Upon his return, he would have been required to swear oaths of abjuration and allegiance to George II by administrative necessity. The procedure was still relatively new. Such formalities were not required of arriving passengers in Philadelphia prior to 1727. (Hinke, Introduction to Strassburger 1934: xxi-xxii)

Consider next the activities of the prominent Clymer merchant mariner and shipbuilding family of Bristol and Philadelphia. Christopher Clymer, captain of the Richard and Elizabeth, which bore the names of his parents, was the father of George Clymer (1739-1813), a friend of George Washington and a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Christopher’s brother was William Clymer, captain of the Philadelphia-built Alexander and Anne.

We have partially reconstructed the transatlantic activities of the Clymers between 1717 and 1745 drawing upon newspaper accounts available only on location at the British Library in London. What emerges from the regular reports of port activities, rife with gaps as they probably are, is a complex network of routes stretching from the eastern seaboard of today’s United States and the Caribbean to the major ports of Europe. Robert Clymer, for example, repeatedly sailed the Elizabeth and Alice from Carolina [an area then large enough to include today’s two Carolinas and parts of Virginia] and Antigua via Cork and Milford-on-Sea to the family’s native Bristol between 1717 and 1722. On the 13th of January 1728, The Daily Journal London published in tabular form the data on 43 ships that had arrived “on the Island of Jamaica, since the 15th of August last [1727]”, including the Alexander and Anne, captained by William Clymer. The Alexander and Anne, as we learn from the table, was a type of brig known as a snow, built in Philadelphia in 1726; it registered at 70 tons, carried two guns, was manned by a crew of nine and had sailed to Jamaica from Philadelphia that summer.

The London Daily Courant’s records for 1730 begin with the Alexander and Anne’s arrival in the port of Deal “from Virginia” on the 17th of March. On the 21st and 22nd of June that year, the London Daily Journal reports that she remained in Deal “with Palatines for Philadelphia”. This is the first express mention of emigrant transport aboard a Clymer ship. Moreover, the dates bracket off an interval of roughly 3 months to complete the journey from England’s southern coast to Rotterdam and back before embarking on the transatlantic return.

The next record of the Alexander and Anne, as published Ralph Strassburger’s 3-volume Pennsylvania German Pioneers (1934), the authoritative source of such arrival information, is that of her arrival on the 5th of September, 1730, at the port of Philadelphia with immigrant Palatine passengers including one “Adam Schuler”. Approximately five months later, her return passage from Philadelphia to Lisbon on the 19th of February, 1731, is recorded in The Daily Journal London. On the 6th of December, the same paper reports that she was back in her native port of Philadelphia. On the 30th of August, 1732, she is in port at Dartmouth, having made her way from ”St. Christopher’s [Leeward Islands] for London in 8 weeks.”

The first appearance of Christopher Clymer’s brig Richard and Elizabeth in these contemporary British newspaper accounts is in The Daily Journal of April 26th, 1733, which reports on her journey from Charleston to Rotterdam via Poole. The southbound leg along the Atlantic coast would have begun in her home port of Philadelphia. Approximately 1,000 miles off the coast of Portugal, she encountered an unnamed ship in distress: “Pool[e], April 23. This Day arrived the Richard and Elizabeth Brig. Clymer from South Carolina for Rotterdam: In her Passage she met with Capt. Rich. Vivian from Dartmouth for Maryland in the latitude 43 and longitude 25 whose Main-mast had been carried away, and she had shifted her Hold.”

Three weeks later, on the 13th of May, 1733, The St. James Evening Post reports the Richard and Elizabeth’s progress eastward and arrival at Dover. From there she eventually sailed on to Rotterdam where the Palatine passengers of her return voyage to Philadelphia awaited her. Perhaps the “Frantz Schuller” of the passenger lists was one of those passengers awaiting her arrival in Rotterdam. But then again … he could have been aboard ever since the ship departed Philadelphia for Charleston.